An Interview with Thom Hogan

#33649

An Interview with Thom Hogan

#33649

01/30/11 12:51 PM

01/30/11 12:51 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

The Nature, Wildlife and Pet Photography Forum

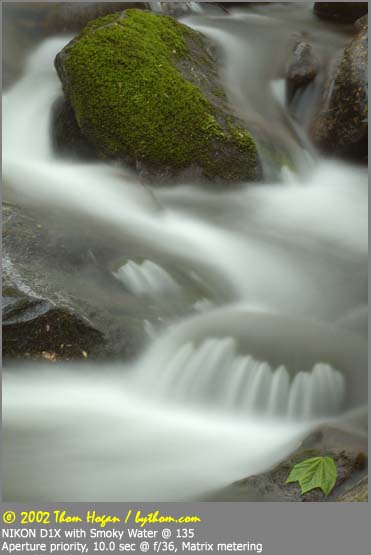

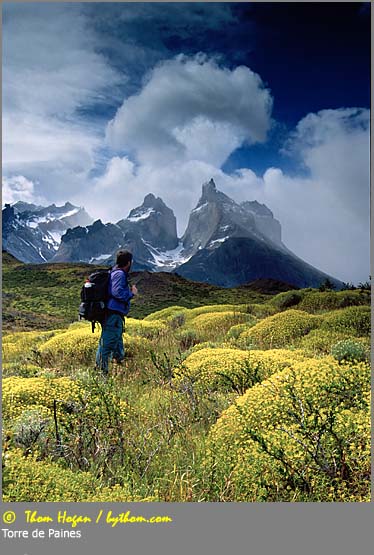

Artist Showcase: Thom Hoganby James Morrissey Please note that this article was our first interview, done in 2005. It is copyright property of James Morrissey and the NWP Photo Forum, and may not, in part or in whole, be reproduced in any electronic or printed medium without prior permission from the author. The images in this article are the property of Thom Hogan and have been licensed to James Morrissey and the NWP Photo Forum for the purpose of this interview. Thom Hogan is one of today's accomplished and prominent nature photographers. He is well published and perhaps he is most well recognized for his Nikon Field Guides. We hope that you enjoy this three part interview, as well as, learn something new.

|

|

|

An Interview with Thom Hogan - Pt1 Bio

[Re: James Morrissey]

#33650

An Interview with Thom Hogan - Pt1 Bio

[Re: James Morrissey]

#33650

01/30/11 01:34 PM

01/30/11 01:34 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

Part I: About Thom  JM: Would you like to give us a short social history about yourself? JM: Would you like to give us a short social history about yourself?TH: Unfortunately, I like to talk and my history is filled with things to talk about, so I'm not sure I can honor the "short" part of the question. (Smiles) I'm an only child whose parents taught him to be independent, curious, and hard working. That was a recipe for an amazing number of twists and turns along the way. The short answer, I guess, is that I've always followed my curiosity, and I'm an incredibly curious individual. Thus, my track record runs across so many disciplines and trails I sometimes forget them all. I like to say my life has been a remarkable random walk.[/color] JM: When and how did you begin with photography?TH: I have my mom to thank there. She's always had an artist side to her (these days she paints), and when she started exploring photography as I was growing up I got curious and did, too. So much so that when my dad and I built a house for us while I was in high school, I designed a dark-room into it. And borrowed my mom's Nikkomat FTN when she wasn't looking. I shot for the school and local newspapers, and then did some photography on the side when I went to college and majored in film making. Some of the promotional stills we used at the television station were my photos, though at the time I wasn't thinking of them as "mine." JM: At what point did you decide that you wanted to be a professional photographer?TH: I'm not sure I have! Being a full-time professional photographer is more work than most people think it is. I'd have to consider myself a part-time photographer and full-time writer right now. But the answer to your question is a story I often tell at workshops: I was in Seattle interviewing for a position running development at Real Networks when I noticed an employee ad in the Sunday Seattle Times-Intelligencer: "Backpacker seeks executive editor. Call John Viehman at XXX-XXX-XXXX." That was pretty much the whole ad. I have no idea how it caught my attention, but it did, and it got me started thinking about switching my vocation (running product development in high tech) with my avocation (enjoying the outdoors and recording my experiences there). I clipped the ad and brought it home with me. I didn't call the number immediately; I remember it being well more than a month before I did, and it was more than six months before I actually joined Backpacker magazine, so finding that ad was just the start of a slow dance. Interestingly, the thing that kicked it over the edge was Galen Rowell. John knew Galen and knew that Galen knew me. Unbeknownst to me John called Galen and asked for a recommendation, which Galen gave freely even though I had never even told him I was applying for the job. That's just one of the many reasons why I continue to try to tell Galen's story these days, by the way--he was a great man, photographer, and writer who influenced many people's lives, sometimes without them even knowing. JM: What types of professional photography have you worked in (i.e. stock, publishing, portraiture, weddings, etc) prior to having developed the camera Field Guides?TH: Most of my professional work prior to the first Nikon Field Guide was actually in film and video. I used to carry a still camera with me, too, and sometimes I'd come away with some good photos. But my first goal was always motion images. I sold a few photos along the way when people would see them and had a need for them, I used a few in publications I put out (I edited a number of magazines and wrote quite a few articles and books along the way), but for the most part my still images sat in my files. When I started taking three-week trips into the wilderness once a year to get away from the pressures of high tech, I started simplifying and just took a still camera. That's when my current interest in nature photography really got started. As for weddings, I run from them, though given my portraiture and lighting skills I'd probably do okay. With wedding photography one mistake and you could be done for forever. With nature photography, you do what you want at a leisurely pace and no one has to see your mistakes (and there will be mistakes).  JM: Who are your biggest photographic influences?</p> JM: Who are your biggest photographic influences?</p>TH: I've already mentioned Galen. Over the course of a little more than a decade I probably spent as much as five or six months with him photographing in great natural settings. It would be difficult to spend that much time with any photographer and not have something rub off on you, but as I've said, Galen was a great man, and things came out of his mouth that just washed over you and overwhelmed you if you weren't careful. He taught me so many things that I just can't begin to mention them all. But the biggest influence he had was in something he didn't teach me, but forced me to learn on my own. There's a tendency when you're at the coat tails of a great master to imitate the master. Galen's most important words to me were that I needed to find the place from which MY pictures came, not his. He had no idea what that might be, but he knew the point when I had the skill set necessary to start figuring it out, and he just started pushing me on figuring that out. Sadly, I now have a pretty good idea what motivates my photos, but I'll never have a chance to have a discussion with Galen about that. I think it would be quite an interesting discussion, actually. JM: Where does your photographic education come from?TH: Galen wasn't the only influence. As I said, I have an undergraduate degree in film making (and a masters in television production), so I've had formal training in imaging and lighting along the way. When I started getting back into photography in the late 1980's after a long period of not having a camera, I also began the practice of taking a University of California extension class once a year. Some were just weekends, some a few weeks, but all were with some extraordinary teachers. For example, James Katz runs a rafting company called James Henry River Journeys, but used to teach weekend classes in Pt. Reyes once or twice a year. Not only is he a good photographer, but he's a good teacher, and I picked up a few things from him I wouldn't have encountered elsewhere. John Senser is a naturalist turned photographer who taught for UC, as well. Some of my favorite Yosemite shots I've taken came while under his tutelage. Unlike Galen, those names may not ring bells, but both actively teach workshops and sell images. And that's one of the interesting things about this business: there really are a lot of good teachers and resources for someone who's really interested in pursuing nature or wildlife photography. Lots. If you don't believe me, check out the Shaw Guides site and be prepared to be overwhelmed with the number of workshop choices you have. JM: Do you have a business education?TH: Funny you should ask that. As part of my Ph D program at Indiana University (in New Technology Economics and Management) I took the MBA course-work. My mentor at the time was trying to get me the training and knowledge that would let me become an executive at NBC, where he consulted. Since you can't get two degrees for the same course-work, given the timing I probably made a big financial mistake by not getting the MBA. (Smiles again) Now, all that seems irrelevant, right? Not really. Sometimes I think you almost need an MBA to make it professionally in photography. Most people really only see the photographs (and occasionally meet the photographer). It looks easy. Heck, it used to only take a $500 camera and a $3 roll of film, so it probably was inexpensive to get into, too. Wrong! If you look behind every successful nature and landscape photographer you'll see a very hard working businessman or woman. The one thing I always envied about Galen wasn't his climbing or photography or running or writing skills; it was the fact that Barbara ran his business and freed him to only deal with his creative side. Me, I'm not only single but don't even have a girlfriend, so I have to run the business as well as do the creative. You see one or the other over and over: either the photographer is paired up with someone who does most of the work in keeping the business side going, or the photographer themself has a very strong business background and work ethic. The alternative is to be a starving artist who's work, if ever, is discovered long after you've passed. Not that there's anything wrong with that if that's what you want. Nature photography can be a soul soothing endeavor. But if you want to do it for money, get ready to work harder than you've ever worked, and most of that work won't be taking pictures. JM: When we were discussing your photographic influences, you commented that when you were working under Galen Rowell's tutelage, he was constantly pushing you to find the place from which your pictures came from. What is it that motivates you?TH: Well, in the main, it's the same thing that motivates every nature photographer: we want you to see what we saw or more importantly, felt. How the place affected us. I suppose my wording before wasn't quite right--when I talked about where the pictures come from, I was talking more about a personal sense of photographic style. Those that have seen some of my more recent work know that I've lately tended towards what I guess I'd call a "we're all small things in a big place" kind of style. I've got a series of photos I've taken I call my Big Sky series, where I take pictures of very recognizable natural icons, but they form a miniscule part of the image. Styles evolve over time, and you respond to different things. I guess to put it properly, Galen was pushing me to make sure my photos were my response to what I was confronted with, not something that mimicked his or other photographers.'  JM: Does this also motivate your personal life? JM: Does this also motivate your personal life?TH: Funny you should ask that. I've been teaching a variant of what I've figured out at my workshops, something very different than what I've seen others teach, actually. It's sort of a mantra short cut to get to your own style and evocation. It only took me 10 years to figure it out, but I can teach it in 10 minutes--go figure. But one thing I realized is that, yes, it carries over into other things. I think that as we mature, we're always looking for ways to explain why we're here, what our role is in the world, and what we'll leave behind. So, yes, I started looking at life just as intensely as I look at nature. And you can see some of the carry over in my dedication to preserving the natural world. I take photos of nature because I want to show the wonders of the world to others who might not have been lucky enough to go there and see them. But my charity work is mostly about making sure that future generations will also be able to go there and see them. I'd be chagrined if some day the only thing left of the view at Admiralty Lake is one of my photographs, not the place itself. Yes, I know places evolve and it'll never quite be the same as the moment I was there, which is one of the reasons why we photograph, but we ought to at least try to have places that evolve naturally, not get paved over for parking lots and condos. JM: Can you share more of how you first met Galen Rowell? You mentioned earlier in the interview that he was called by the editor of Backpacker for a reference on you. Under what circumstances did you know him prior to your beginning to work in the professional community?TH: Well, I have a whole article on that on my site (see <a href="http://www.bythom.com/chasing.htm">http://www.bythom.com/chasing.htm</a>). It really was one of the random events that change your life in ways you can't foresee. Essentially, I got sucked into one of his workshops by accident, and not just any workshop, but a three week tour of Botswana. Thus, right off the bat I spent a lot of time with him, and we hit it off. By the time the Backpacker job came along, I had trekked with Galen in the Andes and met up with him many times on the trail as well as his local gallery and offices. And, of course, I sucked up everything he had written and managed to ask intelligent questions about most of that, which I think impressed him enough to tolerate my hanging around. JM: We were discussing families earlier...at one point, you mentioned that you envied Galen because of his strong symbiotic relationship with his partner, Barbara. You also said that many couples in the photography business are like this. Do you feel that your busy lifestyle has paradoxically prevented you from being able to have this sort of relationship?TH: You bet. I'm either stuck in the office trying to catch up, or I'm out in the middle of nowhere taking photos. I'm also at an age where I'm focused on trying to get things done while I've got the energy and stamina to do so. In Galen's case, he met Barbara when she worked for North Face. She decided the North Face catalog needed shots of people actually using their products, and hired Galen to do that. And they clicked. So I guess there's hope for me yet. JM: More importantly, is it something that you want for yourself?TH: Yes, and I think that every successful nature photographer really has to have some close relationships that work for them, whether they be familial or just friendly. I mean, if you sit in bird blinds for 16 hours a day for a week and that's all you do, you're headed towards that starving artist who's remembered only after death kind of existence, which seems just a bit too unconnected for me. Observing and photographing nature seems to me to be about our connection to it, so if you're disconnected, you'll have a hard time making interesting photos. But you've probably also noticed that I've mentioned more than once in this interview things that speak to my purpose in life. If my purpose in life is just to exist and do what I want to and nothing else, then that's a pretty shallow purpose, isn't it? I'd like to think that I had a positive impact on others, that I shared what I saw and did with others in some meaningful way, and that they had the same affect on me. On Wednesday night, we are going to put up Section II of this three part interview. Section II will encompass the aspects of Thom's business. Section III, which will be published on Sunday night, will talk about Thom's feelings on various environmental issues.

|

|

|

Interview with Thom Hogan - Pt2 on Business

[Re: James Morrissey]

#33651

Interview with Thom Hogan - Pt2 on Business

[Re: James Morrissey]

#33651

01/30/11 01:54 PM

01/30/11 01:54 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

The Nature, Wildlife and Pet Photography Forum Artist Showcase: Thom Hogan by James Morrissey This article is Copyright 2005, James Morrissey, and may not, in part or in whole, be reproduced in any electronic or printed medium without prior permission from the author. The images in this article are the property of Thom Hogan and have been licensed to James Morrissey and the NWP Photo Forum for the purpose of this interview.</p> Part II: Thom Hogan on the Business Aspects of Nature and Wildlife Photography</p>  JM: You mentioned above that you look at yourself as a part-time photographer and more as a full time writer. Do you think that this is the secret of your success? That is, having been able to find a way to make a financial tie between photography and some other career that is related to photography? JM: You mentioned above that you look at yourself as a part-time photographer and more as a full time writer. Do you think that this is the secret of your success? That is, having been able to find a way to make a financial tie between photography and some other career that is related to photography?TH: No doubt. Many people express the desire to become full time photographers but don't really have any way to bridge themselves from what they're doing to what they want to do. They make a leap and often the distance is too great to land successfully on the other side. JM: Do you feel that it is necessary in order to have some other form of 'tie in' business in order to make a life of nature/wildlife photography possible?TH: No. But you need to have the right expectations going in or else you might seriously underestimate the amount of time it'll take to become cash-flow positive, let alone profitable. Let's just say you were really lucky your first time out and caught that wolf/bear/elk encounter that happened in Denali last year. So you call up National Geo and somehow convince them that you're the real thing and have the real goods. A week later they might have the photos. A month later they might decide they want to use one of the photos. A few months after that the photo gets published. A month after that you get a check (for a much smaller amount than you're probably imagining, by the way). Great, you've made a sale. Are you a successful business yet? Nope. You'll likely have to sell those photos many more times in order to even recoup the cost of that trip. But it doesn't end there. Here's another pitfall that happens to newcomers: they can't deliver consistently and don't have the depth of coverage to compete. Following up on our simple example, you've now got a relationship with National Geo. They have another Alaska-related story coming up and they liked your pictures, so they call you up and ask for all your bear photos from Admiralty Island. Say what? You've never been there, so obviously don't have any such pictures and tell the photo editor that. How many more phone calls do you think you're going to get from National Geo? Short answer: none. When I was editor at Backpacker there was a reason why the same photographers names kept appearing (and still do): they were people we worked with who we knew had the goods. Jack Dykinga. Carr Clifton. Galen Rowell. The Muench's. Art Wolfe. John Shaw. That list ought to look familiar, right? They didn't always have the very best picture for something we needed (although often they did), but they always had A publishable picture. So when a few days before the deadline to ship the issue off to the printer the Art Director came up to me and the Photo Editor and said "we need a photo that illustrates X to fill this space," guess who we called? When you asked about whether my writing helped me establish my photography business, yes, it did. But not in the sense you might think. By having a different source of income, I was able to just start stockpiling images. I must have somewhere well north of 10,000 images no one's ever seen at this point, since I didn't have to rely upon photo income. Once I've doubled my library and filled in a few holes, I think I'll be ready to try selling stock seriously and can perhaps back off the writing side and concentrate more on selling my images. JM: You speak strongly about the need for business knowledge earlier in the interview. Short of an MBA, do you feel that there are any essential business basics that may be offered at a local University that people should take prior to starting their own business or to improve their existing business?TH: Well, being able to budget and estimate cash-flow is probably the two best skills you need on the back side. But being able to network and sell are the two skills that'll help you most, and there are plenty of ways to find both formal and informal courses that help you with that. I don't think I'd be wrong if I said that, on average, the successful photographer spends at least half their time networking and selling (or has someone spending equal amounts of time to what they do photographing, which amounts to the same thing). For publication, you need to spend a lot of time sitting down with photo editors reviewing your portfolio--you can try doing this by sending it to them and talking to them on the phone, but you'll find it's a lot easier for them to say modestly positive things that sound encouraging but weren't meant to be that way. You need to stay in constant communication with the photo editors you do develop relationships with, and you need to prove that you're willing to adapt to their needs, not the other way round. If you're selling prints in the art market, you still need to spend lots of time selling, and if you're smart you'll ask lots of questions of the folks browsing through your work. I've seen photographers with great stuff miss sales because they printed the wrong size or priced incorrectly. You're not going to learn what your audience wants without interacting with them. So the answer to your question really is to look for instruction or help with a very specific set of skills. Start with the one you're weakest at (for me, that's networking--only children tend to communicate only when necessary). Community colleges, adult extension classes at your high school, traveling seminars, and self-help books at the library are just a few of the places to start looking. JM: It sounds like you kind of 'fell in' to your work at Backpacker magazine and had a very good run there. At which point did you feel that you could go into business for yourself?TH: What I found at Backpacker was one of the most talented set of individuals I've managed, but because of poor management and lack of focus, one of the least productive. That was a perfect situation for me at the time, actually, and yes, we had a very good run. On almost every tangible measure (circulation, newsstand sales, renewals, etc.), the magazine improved, and I'd say it did so creatively, as well. But the parent company was going through some dramatic changes and my boss started trying to manipulate me and began lying to me. I didn't feel it was the right time for me to go out on my own yet, but it was the right thing to do to get out of the increasingly hostile environment above me in the organization. Timing-wise, it was a terrible time to try to go free-lance. In late 2000 and early 2001 I spent most of my time networking and building contacts at magazines for both my photography and writing. And I was having a fair amount of success. But the advertising market tanked in 2001 with the recession, and magazines began cutting back. I was in Paris photographing a cover for magazine when I learned that the parent company had decided to close it down, for example. By summer of 2001, things were horrible: all of my editor and photo editor contacts said basically the same thing: "we'd love to use you, but we've just had our budget cut and we've got fewer editorial pages to fill so we're mostly doing it with staff and stuff that's still sitting around unused." So I made a quick decision to shift to teaching workshops and writing new books. My first workshop was scheduled for Sept 13 in Pt. Reyes, CA. To give me a day to re-scout the location, I decided to fly out on Sept 11. I had two flight choices out of this area: a non-stop out of Newark to San Francisco and a one-stop out of Lehigh Valley to Chicago and then San Francisco. It was a very tough decision. Essentially I was balanced all the gear I had to carry on-board and the pain of having to terminal hop with it in Chicago versus having to get an hour earlier. As you might guess, the Newark flight was flight 93, which was hijacked by terrorists and crashed here in Pennsylvania. Obviously, my first workshop ended up getting cancelled, since there was no way I could get there.</p> Which brings me back to that budgeting and cash-flow thing: bad things can and do happen. You've got to be prepared to weather the worst possible case and hope for the best. It was a close call for me, as multiple things piled up simultaneously (I learned shortly after Sept 11 that my book publisher was in Chapter 11 and wouldn't be paying royalties). I survived by being flexible, having a cushion, and by running on a very tight budget. JM: Can you elaborate a little on how you worked to accomplish your initial plans? Specifically, how did you actualize your plan to make your business a viable financial alternative to your other career options?TH: Well, obviously, I was scrambling. Having talked to a number of other folk who've made the change, including Galen (he owned an auto repair garage prior to doing photography full time), I can tell you that a lot of us have "scramble" stories. I think the key point I'd want to make to anyone considering a career switch like this is that it'll never quite go the way you plan it. Never. Thus, if you get too carried away and plan out every detail and expect it to happen exactly that way, you're going to not only be disappointed, but you'll fail. Little things need to get on your radar and be addressed. There is always something that can put you on the wrong track if you're not careful. Many photographers stuck with Kodachrome back when Velvia came out, for example. What the photographers weren't responding to was a change in how the photo editors were selecting images. Deep color saturation and even color exaggeration was all the rage in designs, not color accuracy or even fine detail. You see this more in fashion photography than nature photography, but styles come in and out of favor. The important point is to be flexible and observant. JM: How and when did you develop relationships with companies like Nikon? Why not a Canon or Olympus Field Guide? TH: My original Nikon Field Guide was really not something that was externally focused. As I wrote in the intro to the first edition, it came about because I was taking these three-week photo adventures once a year to get away from the tech business, and the first week of those trips I was always finding myself trying to remember details and instructions that worked. By the end of the trip I'd be fully engaged and productive photographically, but then I'd put the camera away for 11 months and forget all that. So the Nikon Field Guide started as notes to myself. It grew large enough and fast enough that I realized that it could be helpful to others, so I sought out a publisher and the rest is history. The Nikon versus Canon thing is easy: I had Nikon equipment, so that's what I wrote about. After the book was a success, I actually asked my publisher if I should put out a Canon version. The answer surprised me. They showed me their figures on Magic Lantern Guides for both similar Nikon and Canon products. The Nikon books out-sold the Canon books despite the fact that Canon product might out-sell the Nikon product. I don't know if that's still true, but I suspect it is. Canon users seem to be a little more inclined to let the camera do its thing while Nikon users seem to be more control freaks, and thus want to know what's happening. That's a very broad generalization, obviously, but when you average it out over millions of users, I think it is still a somewhat accurate conclusion. As for why I continue to cover Nikon but rarely venture out beyond that brand, it has to do with my time versus "owning a niche." Lately I've been grappling with the notion of doing a book on the Canon 20D. But that would come at the expense of something Nikon. Yes, I know a 20D book would do well, but would that come at some cost of people's perception of me as one of the most thorough sources of Nikon information? And what would that cost me long term? JM: Is your current work with the Nikon Field Guides (etc) closely related to what you planned when you started to move out on your own? If not, how are they different?TH: Not at all, actually. If you had asked me on Sept 12, 2001 what my business would look like today, I'd have been 100% wrong. The Complete Guide to the Nikon D1h/D1x was the first I self published, and I did that in the fall of 2001 mostly as an experiment. The book publisher I'd worked with for years was in Chapter 11, I wasn't at all excited about doing the dance finding another publisher (plus that would further delay any money coming in from the project). I'd always wanted to try self publishing, so I did. It didn't seem like a big risk, nor did it seem like a big potential at the time. Since no other work on the D1 was available at the time (remember, small publishers were going out of business and cutting back), it sort of succeeded by just being there. But the dynamics of that success made me look more carefully at it, and I realized that I was probably pretty well positioned to make a real run at it. My mom and dad thought I was crazy. My friends thought I was crazy. Sometimes I thought I was crazy, but I put more energy and effort into it and it became clear to me that I had a tiger by the tail.</p> JM: What would you do differently if you had to do it over again (or would you just rather become an attorney?  ). ).TH: Well, I'd have to tell you many more stories about myself to fully answer that question. But I'm in a pretty good place right now career-wise. Over the years I've tended to move from one thing to another every three years or so, and I don't really feel that urge as much as I used to (it's that curiosity thing). I do think that there were times in my career when I was doing what I thought others wanted me to do rather than what I wanted to. These days, I realize those were the worst days, not the best. You really have to follow your heart and your desires. And you have to be prepared to fail. I may yet still fail. But I'm willing to take that risk for the benefits of enjoying myself, feeling comfortable in my own skin, making my own decisions and controlling my own destiny.  JM: What does your business look like now? JM: What does your business look like now?TH: It's too much a business, actually. When you have to make time to photograph, which I do, you know that you might be overextended business-wise. I've had to find ways to make me more productive, so as to have that time to photograph. I actually look forward to workshops since it's one of the things that forces me out of the office with a camera in my hand. But I also don't dare ignore the business side. My business is still ramping up. If I were to ignore it, it would quickly ramp down, I'm sure. My big goal is to try to get it running a little more efficiently and at a reasonable size that both doesn't consume me and doesn't abandon my customer base. JM: Do you have any advice for people who are trying to start a business in nature/wildlife photography?TH: Talk to Dr. Phil first. Seriously, is that REALLY what you want to do or is it what you THINK you want to do? Sure, there are some absolutely special moments that occur when you're out photographing. I remember sitting contently in the shallows of a small pond in Alaska with hundreds of mosquitoes sucking on my exposed parts while photographing a moose for a couple of hours. I was happy and calm as I've ever been. I also remember how hard it was to get to that part of Alaska, find that pond, and get 40 pounds of gear there. And I also know just how much work was sitting piled up on my desk for me when I got home three weeks later. Successful full-time nature photographers are some of the hardest working, intently focused individuals you'll ever meet. Yes, the pace of business might not be that of Wall Street trading, but it can be just as consuming. So make sure that's what you really want, and if it is, go for it. If it isn't, do what I did for over a decade: take a really nice long trip to someplace exotic once a year and do nothing but photograph. You'll get your nature fix without having to think about the business side of it. JM: What do you think it takes for a person to be able to run a photography business as well as have a family?]TH: An incredibly tolerant family. Look, if you're really serious on the photography side, you need to be in the woods perhaps as much as half the year. A lot of nature photographers are husband/wife teams, yes, but they don't always have children. I think it would be incredibly hard to raise a family while being full-time, especially if your specialty is wildlife, which is going to take you deeper into backwoods than landscape or macro photography might. I admire the ones that have managed to do that, but they are few in number, probably for a reason. You can mitigate some of the travel strain by concentrating on an area and living in or close to it (e.g., some of the Alaskan photographers manage to raise a family because they're there, and it's not really any more difficult to photograph while raising a family there than it is to perform any other job). If you live in New York City, well, I think you may have to seriously consider moving. (Smiles) I said before that many of the successful nature photographers are intently focused. They're focused on their work. Sometimes first and foremost. Galen was an example of this. Barbara removed much of the business pressure from Galen's shoulders, and they never had children (Galen had a son from a previous marriage, though). I don't know how successful he would have been without Barbara or if they had had children. The more extreme places you go--and Galen pretty much defined extreme--the harder it is to put family first. Indeed, Barbara was often upset at just how much risk Galen was willing to take to get the picture, though she tried to hide that. Don't get me wrong, I'm not saying that you have to be a lone hermit, risk your life constantly, and have no consideration for others to be a nature photographer. Far from it. But raising a large family and spending lots of time with them while trying to be a full-time wildlife or adventure photographer is probably far-fetched. You'll need to find a balance between your photographic and family life, and that's going to take some tolerance on the part of your spouse. JM: I know that this question invariably invokes a job interview :), but can you give us an idea of what are your personal goals in terms of your business and your own photographic interests over the next 18 months?TH: Short answer: hold on and do more photography. My publishing business is still growing dramatically, so I don't know now where the plateau where I can relax is (or if there even is one). That's the "hold on" part. But I'm happiest when I've had a camera in my hand for a couple of weeks in a great locale. So I'm trying to find more opportunities to make that happen. Beyond that, I'm at a stage in my life where I've got just enough success to allow me to make strange choices. Would I, for example, take a job at another national publication? Maybe, if it let me do more photography. Would I sell my publishing business to someone else? Maybe, if it got me enough money to do more photography? Sensing a theme here? The more likely scenario is even more dramatic, though. I've tentatively planned to take six months off in 2006 to hike, camera in hand, the PCT. A couple of things have come up that might make me push that back to 2007 or 2008, but I think it'll happen sooner rather than later. And I dream about walking from the top of Alaska to the tip of Patagonia someday, again, camera in hand. I've done bits and pieces of that over the years, but I think the great photographers dream big, not small. Even if you don't shoot full time or want to go professional, I think it behooves all nature photographers to find the BIG project, the one that scares you just enough to make you wake up in a cold sweat in the middle of the night. Jim Brandenburg is a good example, with his photography projects. Find a project that's going to push you and challenge you and motivate you and frighten you and take it on. JM: What do you think it will take to achieve them?TH: To achieve my Great Walk goals, I've got to get some business infrastructure things fixed first. I don't want to start off with a business that's running fine and finish the trip to find the ashes are cold. JM: You mentioned earlier that you have about 10,000 images that no one (but you) has seen and that you are hoping to double that number before venturing in stock photography. Do you feel that it is technically wiser to wait until the selection is larger before beginning to sell in stock, and why?TH: If you're going into the stock business, yes, absolutely. Again, it has to do with how photo editors respond. What you want to do long term is get a group of photo editors to consider you any time they have needs for photos in a particular area. You can't do that if they call and ask "do you have X" and you say "no" more than once. They'll simply stop calling. When you're unknown, things really conspire against you. You can list with some of the places that promote stock photographers (e.g. PhotoSources), but photo editors are not only busy, but they like to be productive and efficient. They do on-line and database lookups usually only as a last resort (and even then they often will go to someplace like Corbis, first).</p> That means that you have to be proactive. You need to get your portfolios into the right photo editors, you need to send regular reminders of your stock coverage, you need to be able to respond immediately when they do call and provide them with what they asked for, not what you want to sell. Now imagine that you've got 1000 saleable images. You might get your portfolio past the photo editor (if you can't, that right there is a big warning sign that you're either not ready yet or you're in the wrong publication). But when you tell them that your coverage consists of a hundred or so images of the Grand Canyon, a hundred of Yosemite, a hundred of Yellowstone, and so on, what are they going to think? First, images of those places available to a photo editor probably number in hundreds of thousands. Why would they use yours? If you can't answer that question, you're not ready. But beyond that, what are the chances that out of 100 images you'll have the image that they're looking for? When we did image calls at Backpacker we'd sometimes get hundreds of images for a particular call, such as "hiker approaching Thousand Lakes in Ansel Adams Wilderness." Is that in YOUR file? Thus, you have three possible approaches to stock. First, you can shoot a lot and build a big database of images. That increases the odds that you have what a photo editor is looking for. Second, you can specialize. Instead of taking a thousand photos of Half Dome and competing with every other photographer in the world, perhaps you specialize in desert flowers. Not only is that a manageable niche, but it is even manageable from a photographic standpoint--you'll be spending an intense month or two every year in some very specific places. Not every photo editor needs desert flowers, but when they do, if you've done your marketing right, they'll know to come to you. Third, you can use an agency. Here, you join with other photographers to provide that coverage, but you also may be competing with them. When a photo editor does a Corbis or Getty search, they often pull up hundreds of matching images, of which yours might be just one. But the agencies don't really want to handle small catalogs--they want a photographer that's got a thousand or more A level images and the commitment to increase that by hundreds or thousands every year. So, you've got to be good. You've got to market well. And you've got to have the goods when the phone rings. JM: How would you characterize your attempts to sell stock photography in the past, if any?TH: Haphazard, at best. I started out with the same notion that a lot of folk do: hey, I've got some really nice images, publishers will buy them. One of the things Galen did with me was to invite me in to his offices after a three-week trek in the Andes we did together. I got to see how he handled the 100 plus rolls of film he brought back, and what happened to those images. First, I noticed how little he saved in his A pile. Second, I noticed that what he did keep went into his files of tens of thousands of cataloged images that was managed by a staff of, I think, six people. That's what I was competing against. And that changed my mind about what it would take to compete. A photo editor could call Galen's offices, get the stock manager and have faxes of images on his desk in minutes (this was the mid-90's; today it would be email) and the images properly bundled up and on their desk via FedEx the next morning (or perhaps FTP'd today if the publication accepts scans). With me, well, was I even in the office to answer the phone or did they get my voice mail because I was out shooting? That's just another reason why I've backed away from trying to sell stock full time. First, I've got enough income coming in that I don't have to do it, thank goodness. But second, I'm not fully prepared organizationally to do it. Only about half of my images are cataloged. I don't have any staff who just deals with my images and managing the logistics with photo editors. Not that you need both those things, but to really make good money off of stock, I think you would. JM: Besides having a large volume, what is the secret of moving stock photography? TH: I said it before: no matter what type of photographer you are, if you're doing it for profit, you'll be selling more than you'll be photographing. If you're always photographing, you'd better have staff and other resources that are doing that selling. Even if you were just doing art shows to sell prints, this is still true. Marketing and sales skills and the time to do them are the things that most photographers try to avoid, but they are integral to their eventual success. JM: Does your name recognition have anything to do with it?TH: Boy, if you have to rely upon name recognition, you're probably better off betting on your state's lottery. Because that's often how name recognition happens: random. They say in Hollywood that everyone gets one shot (it's true of television, too, because it's a black hole when it comes to content creation--it sucks up any and everything to fill the air 24/7). But I don't think that's true of photography. You might never get that shot. Or you might get a truly random shot that suddenly puts you in the limelight. You caught a picture of something rare or previously unseen. You happened to be in the right place at the right time. Some editor picked your image for a cover and others saw it and wondered about who that photographer was. But more often than not you're just not on the radar screen until you put yourself there. JM: Do you feel that there are better companies than others to work with? If so, do you mind naming names?TH: Oh oh. That's a tough one. Let's start with the first question: yes, there are better places to work with, and there are also better places for newcomers than others. The reasons why I balk at the second are multiple: first, there's a never ending change that occurs in the publishing marketplace. A publication that was paying well and on time and treated you well can often change overnight. A new publisher comes in and tells editorial they're spending too much on photos and bingo, things change. Or there's a recession and advertising goes down. Or the photo editor, who was great to work with but isolating you from the real organization behind them, moves to another publication. Every time I've recommended a publication to someone, within two years things were different (and sometimes within two weeks). So I'd rather tackle it another way: start small and local if you can. I'm in eastern Pennsylvania and a publishing company called Rodale happens to be headquartered in my town. Guess where I'd start? But if I were in San Francisco, I'd start with Sierra magazine. Name me a town and I can name two or three places locally that you should start. You probably already know who they are. If they don't work out, expand your circle, but start local. JM: Last, you mention 'sitting down with photo editors' and developing relationships as an integral part of starting an effective business selling photographs. My guess is that for many people who are looking to get in, often times the hardest place to start is knowing where to go to. Do you have any advice about how to find an editor who is willing to take time out of their busy day to speak with an unknown off of the street? TH: Well, I mentioned NANPA before, so this is probably a good place to put in another plug. NANPA has annual conventions and one of the things that you can do at those conventions is get a portfolio review by a photo editor working in the business you're trying to sell to. Photo editors aren't dummies--they realize that it's actually a good use of their time being somewhere where there are multiple new potential sources of photos gathered together, and that describes NANPA to a T. Beyond that, you'll see what others are doing in the open screenings (so you'll know where you stand vis-à-vis your competition), you'll be able to meet and interact with others who are active in the same area as you and compare notes, and you'll be able to rub coattails with some of the name photographers you've admired, who usually turn out to be remarkably approachable and helpful. So start there. But if you have to cold call into the photo editor world, you need to make it easy for them. First, photo editors run hot and cold in terms of available time. They are on deadline parts of the month, not during others. At Backpacker, for example, we published only 10 issues a year, so there were two months during the year when the photo editor was far less busy than others. You need to figure out what those are. So your approach should be along the lines of "I'd like to show you my portfolio and get your comments, but I'd like to do that at a time where you don't feel rushed, busy, or on deadline. Can you tell me what's the best time and method to approach you?" If your approach is "hey I've got a portfolio you need to see, can I come in this afternoon" you'll get shut down so fast it's pitiful. Be respectful. Find out what works for them. Try that. Then be gentle but persistent afterwards. And if you get face to face or telephone time with a photo editor, always be asking questions along the lines of "what do you need," "how do you want it," "how can I better work with you to meet your needs," and so on. Photo editors appreciate photographers who make their job easier. On Sunday night, we are going to put up Section III of this three part interview. It will talk about Thom's feelings on varoius environmental issues. To read more about Thom go to By Thom .

|

|

|

Interview with Thom Hogan Pt3 - The Environment

[Re: James Morrissey]

#33688

Interview with Thom Hogan Pt3 - The Environment

[Re: James Morrissey]

#33688

01/31/11 08:01 PM

01/31/11 08:01 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

The Nature, Wildlife and Pet Photography Forum Artist Showcase: Thom Hogan by James Morrissey This article is Copyright 2005, James Morrissey, and may not, in part or in whole, be reproduced in any electronic or printed medium without prior permission from the author. The images in this article are the property of Thom Hogan and have been licensed to James Morrissey and the NWP Photo Forum for the purpose of this interview. Part III: Thom on the Environment  JM: I have read several of your articles that were posted on the internet about wildlife and nature conservation. It is obviously an important part of your value system. What do you list as the top dangers to the National and State Parks? JM: I have read several of your articles that were posted on the internet about wildlife and nature conservation. It is obviously an important part of your value system. What do you list as the top dangers to the National and State Parks? TH: Oh geez, there are so many that come to mind that I might end up talking for hours on this subject. Overall, the issue that comes to the forefront for the National Parks since President Bush took office is that funding has been in jeopardy and privatization is being pushed. While the Bush administration may point to some funding increases, you have to look at where those increases have gone and what's still underfunded. Much of the NP money has gone to or is destined for (needed) infrastructure issues--plumbing in Yellowstone, the Going-to-the-Sun road in Glacier, and so on. Huge backlogs of such maintenance projects exist, with hundreds of millions of dollars of still unfunded items to be accounted for. At the same time, funds for preservation of back-country, natural research, and even rangers on the ground (other than for things like police protection) have disappeared. The net result is that, in some parks, rangers and even part-time summer workers who had the most knowledge of the biological, natural, and historical aspects of our parks no longer work in the parks. They've been replaced by more front country personnel dedicated to visitor comfort (food and lodging provided by private companies) or not replaced at all. The bills that established the National Park system all speak toward preserving and protecting for future generations. What I see is an effort to make casual front country visitation more painless and more about looking at a few big features. Yosemite is a huge park, but few ever see anything more than Yosemite Valley (front country), and the remainder often see little more than what's along the road to Tuolumne Meadows. That's a shame, since Yosemite contains an amazing variety of terrain and features, most of which are only accessible by trail. I'm not against making the front country more accessible, but I am against making that the priority over all other aspects of park management. In the state parks, the issue is easier to identify: there's a swing right now towards the federal government cutting funding to the states (and it's not exactly well proportioned as it is, with California only receiving 70 cents on the dollar back from the federal taxes CA citizens pay). The states have the same fiscal crisis the federal government has: health care, retirement, and other social expenses are increasing dramatically at a time when the funding for those is either level or dropping. Some states, such as California, self-imposed funding issues (Prop 13 comes to mind) that further hampered state funding. The result is that many of the states are jettisoning funds to anything that doesn't move, and that includes the state park systems. Short term, we can withstand that kind of neglect, but long term it is very dangerous--we could end up with parks that are nothing more than parking lots with picnic benches and which don't even have toilet facilities because that would cost money to clean and monitor. So it's a lot about money. If the government won't step up to the plate, we citizens have to. I suppose you could think of it as a self-imposed tax increase. I've put my money where my mouth is. Starting in 2004 I've dedicated 5% of my profits (actually, in the end it turned out to be more) towards projects that affect the areas I photograph in. And you can help me with this. In 2004 I started the Galen Rowell National Trails Fund, a permanent trust fund dedicated to providing money to keep trails and access in wild areas open and maintained. I put in enough money up front to make this a permanent endowment--at present it offers US$500 grant each year. Don't scoff at that--most trail maintenance is volunteer work, so that money buys much more than it at first seems it might. But you can help make that amount increase. The Galen Rowell National Trails Fund is open to others. If fifty of you reading this each contributed US$10, that would replenish the initial trust, and due to interest, make for a larger grant next year. The fund and the grants are monitored and chosen by the American Hiking Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to local and national trails. To contribute, just go to www.AmericanHiking.org and fill out the required information. PLEASE MAKE SURE THAT you add a note or comment that your money is to go to the Galen Rowell National Trails Fund--AHS maintains many trust funds, so you'll want to make sure that your money gets to the right place. I fully intend to continue doing something different each year (i.e., in 2005 I'll fund a new initiative). My hope is that I'm planting lots of little conservation seeds that'll bloom for generations to come. JM: What ideas do you think a group like NWP (and others here on the net) can do to promote real environmental change?TH: Well, aside from contributing to the fund I just suggested, you just have to get involved with something, anything, at your local level. The Sierra Club has local chapters everywhere. Most state and federal parks have docent or other volunteer programs you can get involved with. Call up the biology department of your local college and find out who's doing natural research and arrange to talk to them; offer to help document their research with your photos. If you live near ANY wildlife refuge, national monument, or other designated lands, just go down to their local office and find out what they need and ask them how you can help them. You'll not only help them, but you'll help yourself. Here's the dirty little secret: almost all of the successful nature and wildlife photographers have close relationships with land managers, researchers, and others involved with our wild lands. That's how they know where to go and when! Indeed, if you develop a good enough relationship with one of these folks, you'll often be invited along on monitoring or research trips that provide once-in-a-lifetime photography opportunities. As for NWP, organizations best serve as matchmakers for what I have just talked about. Find 100 researchers who need documentary, monetary, and logistics help and link them up with budding photographers. (This mimics what AHS does with trails, by the way. AHS has funding sources that it tries to link up with those needing funding, amongst other things.)  JM: Would you like to talk about the American Hiking Society and what your role is with them? JM: Would you like to talk about the American Hiking Society and what your role is with them?TH: Well, I already have. (Smiles broadly) But there's more there that's worth talking about. AHS has a program called Volunteer Vacations. If you're prepared to work your butt off while having the time of your life in some wonderful photographic locale, there's not a better bargain on the planet. You WILL work. I had to burn all my clothes from my Admiralty Island Volunteer Vacation because they were covered with sap, bug juice, and ripped in so many places I stopped counting. But in between swinging the scythe and ax I managed to also rip off some incredible pictures I wouldn't have gotten otherwise. JM: Are there any small philanthropic organizations that you know of that do not get much press, but do great work, that you feel should be mentioned?TH: That's a good question. I'm not sure anyone's really compiled a good list, and now you've just put another darned thing on my to-do list. (Laughs) Short of me providing that list, why not make NWP the repository of such a list? If everyone reading this can come up with one or two worthy organizations and you do a basic vetting on them, you'd have something that simply doesn't exist for nature photography right now. NANPA (North American Nature Photography Association) hasn't even managed to do that, to my knowledge. Hint, hint: if you're reading this and not a member of NANPA, you should be. If you mention my name when you join, I'll get NANPA bucks as a reward, but here's what I'll do: I'll donate those NANPA bucks to some photography student somewhere--that way we'll all benefit. Thanks again to Thom Hogan for having done this interview with us. As I said earlier, he was the first person to grant us an interview and I will always appreciate that. To learn more about Thom, check out his website, ByThom.com

|

|

|

|

|

0 registered members (),

250

guests, and 2

spiders. |

|

Key:

Admin,

Global Mod,

Mod

|

|

|

Forums6

Topics628

Posts992

Members3,317

| |

Most Online876

Apr 25th, 2024

|

|

|