Part I: Alain Briot Interview with NWP

[Re: James Morrissey]

#35798

Part I: Alain Briot Interview with NWP

[Re: James Morrissey]

#35798

07/17/11 04:24 PM

07/17/11 04:24 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

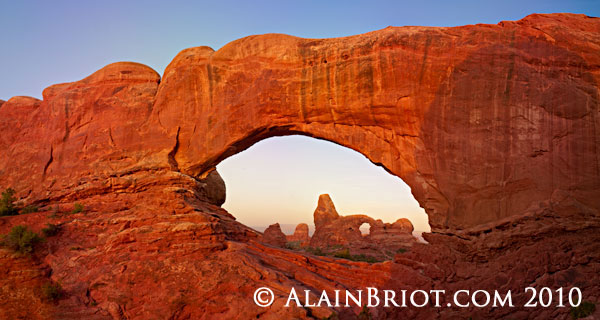

We are trying to develop a community where photographers can come and discuss nature, wildlife and pet photography related matters. We encourage you to enter forums to share, make comments or ask questions about this interview or any other content of NWP. The Nature, Wildlife and Pet Photography Forum Artist Showcase: Alain Briot by James Morrissey This interview is Copyright 2006, James Morrissey, and may not, in part or in whole, be reproduced in any electronic or printed medium without prior permission from the author. The images in this article are the property of Alain Briot and have been licensed to James Morrissey and the NWP Photo Forum for the purpose of this interview. Part I: About Alain Briot  (c) Alain Briot JM: Would you be willing to give us a short social history of yourself, talking about your family and what life was like when you were growing up? AB: I was born in France in 1959 and moved to the US in 1986. People often wonder why I left France. France is a wonderful country but it just didn't offer, and in my estimate still doesn't offer, the opportunities I was expecting. Anyway, I was born near the Montparnasse district of Paris. Today, mostly immigrants live there. When I was born Artists lived in this district. Times change and with it a lot of the romance of Paris, though much survives. Stereotypes also survive. Montmartre was not, and is still not, the only haven for artists in Paris. Montmartre is where a lot of artists work and sell their work. The fact is, most of them cannot afford to live there. My parents, who were also artists, couldn't afford to live in Montmartre in 1959 already! My mother was a trapeze artist. My father met her when he took a job as accountant for the Cirque Bouglione where she worked. She went on to work for Shepherdfields, in England, and since they didn't need an accountant --they already had one-- he studied magic and learned several tricks that he performed on stage for them in England. When they went back to Paris, and later when I was born, he returned to mathematics and became a world-renowned engineer in noise and vibration control. He made very good money and was able to pay my way through schooling in the US. That's how I came to live in the US. JM: When and how did you first begin to photograph? AB: Let me change the question to "When did you first begin to create art?" Too often people make a difference between taking photographs and making art, be it painting, drawing, music, architecture, sculpting, ceramics, etc. That is fine if you don't consider the type of photography you do to be art. However, to me, the photographs I create are art. And if you must ask, yes, I believe that photography is art and I can prove it. In fact, I am doing just that in my new "Reflections on Photography and Art" series. If you have not read it yet here is the direct link to the series' introduction. One of the upcoming essays in this series is about “Why photography is art”. Anyway, I remember making art from as far back as I have memories. I used to look at my mothers paintings -watercolors, pastels and oils- as well as at the costumes she had made and wore for her trapeze acts. She had kept a large collection of loose sequins, beads and glass jewels. These were used on her costumes as decorations and embellishments, in part because they were beautiful, and in part because they were highly reflective and caught the light from the circus projectors. I also remember looking at photographs of her on the trapeze, all in black and white at the time. I suppose my first exposure to photography, to photographs that I could perceive as such, was with photographs of my mother. I made my first painting when I was around 5 and continued to paint from then on. I got my first camera when I was around 7 or 8. It was a Polaroid Land 80 camera. I still have it. I remember going out with it in the winter and having to use the aluminum folding print warmer to keep the film warm enough so it would develop outdoors in the cold. We use to put it under our arms, under our clothes. There was a magical technical quality associated with making Polaroid photographs that somehow merged perfectly with the circus and mathematics ambiance in which I grew up. A mix of art and science was surrounding me from very early on! It has been sort of the thread I have followed from then on. I see photography today as being both an art and a science and my goal is to do both equally well. There are just too many people that do either one or the other well, but not both. Most of the time the science part is what people master to the exclusion of art but I also see some mastering the art part to the exclusion of the scientific aspect. Neither work. You have to have mastery of both. In a way my upbringing, my family, were metaphorically a living example of what my current profession requires me to do. JM: Who were your photographic influences, personally and professionally? AB: First my parents, as I just explained. Then my teachers at the Beaux Arts, since again I do not differentiate between studying art and studying photography, and finally Scott McLeay who was my first photography teacher. I attended classes with him at the American Center in Paris from 1980 to 1983. He was a fantastic teacher, and I find it often quite uncanny how my own experience as a professional photographer today mimics his own experience, in so far as the stories he was relating to us in his classes and during conversations. At the time, when I studied with him, these were enlightening stories. Now, they come back to me at times when specific incidents happen or specific situations develop and at these times I go back and remember what Scott told us and how accurate his assessment of what photography is as both a field of expression and a business really were. I wish I could find his whereabouts today but I lost track of him and I can't seem to find the thread back to him. So if you are reading this and you know something about Scott McLeay email me: <a target="blank" href="mailto:alain@beautiful-landscape.com"> alain@beautiful-landscape.com. JM: Do you wish to cite any photographic resources that speak to you? AB: My website is a powerful resource in regards to what interests me today which is photography as an art form. I now publish several series of essays on photography as art, and in a sense they border on philosophy at times. It is interesting how I am returning to philosophy and also to rhetoric after a long time focusing on photography for photography's sake. Eventually my studies have become part of my art. They are merging. I was trying to achieve that through academia, merging my PhD studies with my photographic work, but realized I couldn't do it in an academic environment for several reasons, so I decided to stop that and do what I really wanted to do which was create images and make my income from photography. Eventually, it turned out that through that decision -to do exactly what I wanted- I was able to achieve my original goal. The moral? Do what you love. I tell people that all the time and they look at me like I'm insane. The fact is, I know exactly what I am talking about because I did just that and I have been extremely successful because of it, both in financial terms and in terms of doing exactly what I want with my art, be it writing, photography, teaching, and more. Another resource which I think is fantastic is The Luminous-landscape.. I have worked with Michael Reichmann since 1998, I have seen his site grow over the years, and I think that what he has achieved with luminous-landscape is nothing less than remarkable. Michael gave me the idea for my first series of essays published on his site: “Photography and Aesthetics.” This is a 12 part series which is now completed, except for the final essay “Being an Artist in Business” which is proving to be extremely difficult to write, in part, I believe, because this is a subject that I am still working out in terms of my understanding of it. This month, in November 2005, I created a new multi-part series titled “Reflections on Photography as Art” which Michael will also publish on luminous-landscape and which will be announced in mid-December, when Michael returns from his photographic expedition to Antarctica.  Celestial Star Trails JM: How were you educated photographically? I know you mention on your website the fact that you went to Michigan to get your PhD. However, it does not mention what you were going for or if you completed (or are still completing). AB: I touched upon this above so I won't repeat what I already said. I had a lot of formal education. In fact, up to the end of my PhD studies, I had been a student for nearly my whole life. I never had a formal regular job, or any job that one could consider a career. I worked for my father in France, and did a few things for money here and there, and then worked as a teaching assistant, teaching English 101, photography, digital photography and technical writing, during my Master’s and PhD studies. In a sense teaching was my first real job, but it was so close to studying, I was paid so little for it, and I enjoyed it so much that I have a hard time thinking of it as work. So, in a sense, it is when I decided to make a living as a photographer that I got my first job. And then I was the boss. So maybe, I never really was an employee. I'd like to think of it that way. It makes me feel better. I fare quite poorly as an employee, so thinking that I may never have been one for real makes me feel quite good. But I digress. Let's go back to education. So what I was saying is that I have been a student all my life up to when I ended my PhD studies. After High School in France, or the equivalent of High School which in France is called the Lycee, I went to a private art school - The Atelier Baudry, located at Rue D'Enfer in Paris- to prepare for the entrance exam for the Beaux Arts. Having passed this exam, which consists solely of painting and drawing tests, over several days, I attended the Beaux Arts. After graduating I studied photography with Scott McLeay, then traveled in Europe and the United states extensively, for up to 6 months at a time. I made my first visit to the US in 83, traveling throughout the West for 6 months. In fact that is what got me hooked, so much so that I came back in 86 as a student. I applied to, was accepted, and attended Northern Arizona University (NAU) in Flagstaff. At first I was enrolled as a photography major, but I soon realized that I preferred to learn landscape photography in the field and changed my major to Journalism. After a year, I realized journalism didn't have a substantial theoretical component, and since I didn't want to become an active journalist, the practical part of it did not interest me. So I thought "what could be the most challenging major I could choose?" and I decided it had to be English since excelling in a language that is not your native language is very difficult. So I transferred my major to English and graduated with a BA in English in 1990. I immediately followed up with a Masters in Rhetoric. There is a lot of confusion about what rhetoric really is, so just to set the record straight rhetoric is the study of language from the perspective of motives. Aristotle defined it as the art of language, and in Greece, at his time, rhetoricians were also philosophers. So rhetoric and philosophy have a lot in common, but I like rhetoric better because it is, in a sense, the practical application of philosophy. It is focused on the study of motives -why we say what we say- and can be applied to any form of language, not just verbal, but also musical or visual. As such, it can be applied to the study of photography as a form of visual rhetoric. After getting my Masters I went on to apply to a PhD program, and what I just described is exactly what I proposed in my letter of intent. I was accepted at Michigan Technological University (MTU), in Houghton, in Michigan's Upper Peninsula, also called the Copper Country or the Keweenaw Peninsula. It was the only university at the time that offered a PhD program in Visual Communication. My emphasis was on landscape photography as visual rhetoric. I actually had to make the point to the chair of my PhD committee that visual rhetoric is a reality so that they would agree that this is what I was going to study in their program. You would have thought that since they accepted me on the basis that I was going to study visual rhetoric they would know what it is! Fact is, they had no idea what visual rhetoric was. That should have sent a signal that something was amuck, but at the time I just thought it was glorifying that I had to explain something to the Chair of my PhD committee, that I knew something that he didn’t know or didn’t understand. At the time I saw this as a positive event while in fact they were quite doubtful of the validity of the whole concept. Just as an aside, in the same department, a second member of my PhD committee was teaching French Postmodern Theory using texts she not only had never read before, and was actually reading during the class as she was teaching, but also texts that she actually admitted not understanding at all, and admitting this in the classroom on top of it! That was the measure of it. I had read the same texts several times before as a master's student, in the original version, and felt very confident about my understanding of them. By attending this specific class at MTU I expected to further my understanding. In fact, I ended up explaining these texts to the "teacher"! The fact is, when it comes to assessing the two different universities I studied in, NAU and MTU, that NAU was head and shoulders above MTU, even though I was a Bachelor and a Master student at NAU and a PhD candidate at MTU. The fact a PhD is more work than a Masters is not an accurate gauge of the quality of a university program. If I had to make a comment about MTU today, in regards to the Rhetoric & Communications Department, I'd say they didn't know what the heck they were doing! In fact, when I try to think of who in the MTU faculty had a lasting influence on me, I can hardly think of anyone. Certainly, when I was there, they had an importance. They were running my ass around! But now that this is over, I am unable to say that I think of them as those who helped me make breakthroughs in my thinking, or helped me along on my way. The only person I can think of as having had a lasting influence is Joe Kirkish. Joe was the previous Photography professor at MTU. When I came in he had just retired, and I took up his job, so to speak, except I got the pay of a Teaching assistant, which is virtually nothing, had to teach English 101 on top of teaching photography 101 and running the darkroom, and had to complete all the requirements for my PhD program, which involved taking 3 PhD level classes per semester and completing all the requirements towards the PhD, which are many such as forming a committee, writing a detailed program of study, taking written and oral exams, presenting papers at conferences, meeting with my committee, and much more that I either forgot or repressed. Anyway, Joe was still working as a photographer, and I visited him several times at his house that was nearby. He was selling his work at shows around Michigan and particularly the Upper Peninsula since this is where he lived. Joe was an interesting example of someone who had gone through an academic career, had retired, and still pursued his passion for the arts and for photography. Somehow, academia had not rooted this passion out of him as it does for so many others. I was so busy back then that I didn’t have time to really look at how and why this happened in depth, but I did understand that he never quite merged with the academic community. In fact, as a photographer, he probably was not perceived as a full-fledged academic. For that, you have to do research. All what Joe was doing was create photographs, run the darkroom (which was a complete mess when I got there) and teach photography. He was focused on the practical aspect of things, not on the theoretical. He’s still around, I think he’s about 80 years old now, so he also managed not to die of a heart attack or of some other disease induced by a lifestyle were research comes first and health second, an occurrence which is quite common in academia, that and alcoholism which is rampant, at least at the time I was there, in Humanities departments, especially in English departments, and that across the country. Notice how in all of my studies I managed to live in some of the most photogenic and beautiful locations in the world: Paris, The Grand Canyon, the Colorado Plateau (Flagstaff is 75 miles away from the Grand Canyon and is located on the Colorado Plateau, which is why I chose to study there in fact), the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and later (we'll come to that later on I am sure) Navajoland. It doesn't get any better than that and it sure made my life a lot more enjoyable both in terms of where I lived and in terms of photography. So, anyway, I moved on to doing a PhD. My goal was to merge my studies with my love of photography. I thought this was my last chance to do so. But, as it turned out, that didn’t work. I realized after 3 years of PhD studies that it was either academia or photography, but not both. At least not both in the sense of being both an academic and a professional photographer. I was either going to become a great academic or a great photographer, but not at the same time. And the way things were going, it was clear that academia was taking over big time. So I made a choice, moved back to Arizona and started a photography business. In retrospect that was the best decision I could have ever made. JM: This may seem like a silly question, but do you feel that having grown up in Europe that you have a different perspective on your photography than if you had grown up here in the US? AB: Yes, in the sense that studying the arts, and developing an appreciation for the arts, is a lot more common in France than in the US. In the US some schools don't even have an art program at all. Also, US cities don't always have a budget for purchasing art. In Paris, you find art in the streets, just about anywhere you go. Just about every city in France has some form of public art. It is usually sculptures, but it also extends to architecture, public concerts, theater plays, festivals, and more. Art is part of life. It's not something you find only in museums, or something that one focuses on after reaching a certain income level. Art isn't associated with income as much as it is in the US because having access to art is a lot easier and in many instances it is free. So yes, I think it made me who I am really, by having contact with art since as far as I can remember, and also by being able to create art without having to worry about making money from art. JM: What motivates you in your photographic work? What are you looking for in your photography? AB: Beauty, and more specifically natural beauty. Beauty in nature, in the trees, the rocks, the sand, the canyons, the skies. Beauty above me and under me. Beauty all around me as the Navajos sing in the Beauty Way Ceremony.  JM: What do you think makes your work distinctly different from others covering the same areas? AB: Well, I am Alain Briot ;- ) People smirk when I answer this question that way (I have been asked several times before). They mistake confidence for arrogance. I am very confident. But really, I think that yes, what makes me unique is myself, who I am. How could it be anything else? So, to answer your question more precisely, let me give you some specifics about who I am. In short, I am an artist first and foremost. I made this point already, several times, because it is crucial to me. So yes, that is what differentiates me from many other photographers. I see myself as an Artist who currently uses photography as his medium. I also see myself as a student of photography. Again, people smirk when I say that. I had one of my students say, when I told him that I was a student of photography, "but I thought you knew everything already!" Well, no, no one ever knows everything. In fact, very often the more you know the more you realize how much more there is to know and how little you really know. This is where I am, and this is one of the subjects that is at the center of the essays I write, especially my latest series "Reflections on Photography and Art." I reflect on photography in order to learn more about it. Certainly, I know a lot about it, and this is what allows me to engage in these reflections. But I want to know more, and by reflecting I am creating new knowledge. So this is another thing that makes me very different, my interest in photography as a field of knowledge, as a field that isn't understood very well yet. My writings are certainly something that sets me apart, especially because I do not write only about photographic technique. I also write extensively about the artistic aspect of photography, and now about the philosophical and rhetorical aspects as well. In my eyes, the only author who engaged in the kind of reflections I engage in is Roland Barthes. But he was doing it from the perspective of semiotics, the study of signs. He was looking for signs in photographs, among other things, and how these signs informed the meaning of the photographs he was looking at. Barthes was not a professional photographer. He was a student of language using semiotics as his approach. He was also an art critique. I am a student of language using rhetoric as my approach. I am also a working photographer, deriving 100% of my income, a very good income from photography. So this places me in a different position, the position of a practitioner who reflects on his own field, and a practitioner professionally trained to be a critical thinker with a vast knowledge of critical, philosophical and rhetorical theory. My knowledge comes from both formal studies up to the PhD level and second from actually practicing the profession that I am talking about, not just learning about it in books or through conversations with photographers. There is no substitute for real-world experience. And there are very few people out there making the kind of income I am making from the sale of fine art prints. Finally, to my knowledge there is nobody doing that and looking at photography from a critical and rhetorical perspective. So in that sense, I am unique, and I don't think I have much to worry about in terms of competition. If you think I'm being pretentious let me ask you this question: have you read Kenneth Burke? Or, have you ever heard of Kenneth Burke. Hardly anyone has, and yet he is arguably one of the most important, if not the most important American Rhetoricians. As an aside, I want to add that I love critical thinking, critical theory, philosophy and rhetoric. I had excellent teachers, such as Tilly Warnock who now teaches at University of Arizona in Tucson, or Victor Villanueva who now teaches at Washington State University. Both taught at NAU when I was studying for my Masters. But, in and out of themselves, these fields are, to me, utterly boring. I need to apply them to a real-world situation, to an activity that I can do with my hands for creative reasons. I need a looking glass, if you will, to implement them, and this looking glass is landscape photography. It works for me in this sense. It provides me with all the material I need for a long and valuable reflection. Plus, since I am not affiliated with any university or other academic organization, I don't need to cater to any of the concerns that academics have. I can just do my own thing, write what I believe in, and share the exact outcome of my reflections. You may ask "Why photography?" Why not politics, or social studies, or some other occupation that involves people, power and the pursuit of happiness? My answer is that it is photography because it is first an art, and art is at the center of my life, and second because it is the one art that is the most popular at this time in the history of the world, at least in the Western world. It is also the art form that I practice primarily. The fact that a lot of people don't see it as art doesn't matter. What matters is that they are using photography as the way, and usually the only way, to depict the world, their world. And when it comes to landscape photography, and more specifically to the students that attend my workshops, to the other photographers I work with, and to the people that collect my work, I believe that what they do is embrace photography as a form of personal expression, as a release from the pressures of today's world, and as an art. The fact they often say "I don't do art" in one way or another, doesn't mean they don't. They do. What it means is they don't want to get into that, they don't want to become overly serious about it or get involved in conversations about what is art and what isn't. But the fact is that they are artistes. And to me that is all that matters. The fact that art has a bad name is certainly part of the reason why they say it's not art, but that is another discussion altogether. You also asked what is different in my work from others covering the same areas. I think one thing, which is very different, is again that I have had a unique experience with this landscape, either the American West, or the Upper Peninsula, or other. This different experience is that I lived for years in each of the locations that I photographed so far. I lived 3 years -three 20-below-zero winters!- in the Upper Peninsula, and 7 years in Navajoland. That's living there 365 days a year, not just part time. In fact, I spent a total of 18 years in Arizona, with up to 90 days a year at the Grand Canyon, in the park, not just around but also along the rim, during certain years. I am one of the very few Parisians (sic.) to have lived in Navajoland -in Chinle, at the mouth of Canyon de Chelly to be precise- for 7 years. Although we now live in the Sonoran Desert, we have never quite left Navajoland. There comes a time when you live there when you make this decision, and it is a conscious decision, that you'd rather stay there, good and bad, than leave. We left physically because we wanted our own house (you can't own a house, or land, as a Belagana [white person] on Navajoland) and because running a business, especially one that does well, is nearly impossible on the reservation. In fact, you are not even supposed to have a business as a Belagana! But this put aside, we really came onto our own on Navajoland, and in a sense this is what made us what we are today. As individuals, we were shaped by Navajoland and by its people. As a photographer, there is no doubt that my work was shaped by Navajoland as well. The two -who I am and the images I create- are inseparable. One shapes the other and vice versa. So, to answer your question, I think that looking at my work, at my Navajoland portfolio for example- one should be able to say that this is the work of someone that didn't just travel there for a couple of weeks or month. Now that is not for me to say, that is for my audience. Here is the link so you can see the portfolio for yourself. JM: When did you decide to take your work professionally? Were there periods where you debated stopping and doing something else? AB: I had an epiphany three years into my PhD studies, which I talked about earlier on. At that time, as I previously explained, I was overworked, underpaid and not very happy with the situation I was in. I drove a beater, lived in a run down house that I rented with Natalie, my wife, was deeply in debt, and didn’t see a way out of this situation. So I went to see one of the members of my PhD committee, which I knew was very open to discussing his personal and professional life. I told him what I was going through, and explained that I thought it was worth it since things would get better once I received my PhD and got a job as a full-time professor. I expected that once I got a full time job I would be working less and be getting paid well.  Navajoland Commuting His response stunned me: “No it won’t be less work, it will be more work.” “What do you mean I asked?” ‘Well, once you are hired as a professor, you’ll have to teach classes just like you do now, and you’ll have to continue studying –post doctorate studies for example- and on top of that you’ll have committee work, with a minimum of 3 committees and usually more, you’ll have your students and graduate students so you’ll have to be on PhD committees as well, and you’ll have to do all you need to do to get tenure, meaning presenting papers at conferences writing essays, being published etc. because if you fail at your tenure, which you have to get within a defined period of time, you don’t really have a second chance and you are basically out of a job.” So I said, “well, at least I’ll make more money. How much do you make?” I can’t remember what his exact answer was, but it was around 35K a year. I think I pretty much made up my mind, right there and then, when I heard his answers, to cross out academia as a field of endeavor. The workload was ridiculous and would have left me with hardly any time for photography, which was a serious problem, and the pay simply wasn’t ok at all. I expected 100k or more, not 40k, as salary after a lifetime of study. In fact, once I started my photography business, I started making a six-figure income after a few years. I had a very fast rise in terms of income, something which is not typical, but I proved the point that I could easily out do an academic income within a short time. I remember Victor Villanueva telling me, while I worked on my Masters degree, for which he was my advisor, “ years from now I will still be a f*****g academic and you will be making money.” At the time I thought it was a strange statement, essentially because I imagined myself becoming an academic. Today, I see it as a prophecy, because he is still an academic and I am making money. So he was right. He could see something then that I couldn’t see and I commend him for that. This is the mark of a great teacher: to see where students are headed even though they are convinced they are not going in this direction themselves. It is called vision, and we could use a whole lot more of it! What my understanding was, when I decided to stop my PhD studies, was that anything I would do and do well was going to be a lot of work. So, this being the case, I realized that I might as well do exactly what I liked. It would be a lot of work, and I may not be sure of the outcome, but at least I would have the satisfaction of doing something I really wanted to do. It is this simple understanding and decision that are at the beginning of everything I have done in photography and in my life since 1995, the year I left MTU. And it is this very understanding that continues to shape my decisions in regards to what I decide to do and not do today. If I don’t really love doing something, then I don’t do it. Some people see this kind of approach as being a luxury. They think I am in a privileged position where I can pick and choose. They don’t realize that if I am in a privileged position it is because I placed myself in this position and that I took significant chances in doing so. In my view, this approach is what makes me successful, and I have plenty of evidence to prove that it does. Some do things because they think it will make them successful. I do things because I love doing them and this in turn makes me successful. Some think this is over simplistic, that there is more to it than that. But when you really sit down and think about my approach you realize that there is really no reason why it wouldn’t be so because when you do something you truly love, something that you really want to succeed at because it matters to you immensely, you give it all you have. You work at it because you want to, not because you have to. And it is this approach that makes you successful: hard work, passion and never ever quitting. And you can only have this approach when you do something you truly care about, something you have a personal stake in. So I recommend my approach to anyone who is wondering what to do. Find what you truly love, what you really want to do, whatever that might be, and do it. And if you do it the way I do, which is to give it all you have, and to do it as a passion, I really don’t see how you can fail. In fact, I think you’ll be quite surprised at the outcome. The only thing that worked in my favor and that I couldn’t control was that when I started I had a very low income. I was making about $500 a month in 1995 as a graduate teaching assistant (GTA). So, as soon as I started selling my work, my income went up. A couple of sales and I had $500 in my pocket, and soon a whole lot more than that. And even when you deduce expenses and the cost of creating the work, you still have a very significant profit margin because photographs are not very expensive to create. What is expensive is the equipment. The paper, the inks, even the frames and framing supplies, are quite affordable. Of course, if I had made a good income in my previous job, it would have been harder and taken longer to make more money. And I think this is the situation people refer to when they say I am privileged. They think how much money they would lose if they quit their job today and tried to make a living in photography. I was only looking at how much more money I would make. In fact, I set a very realistic goal, which was to make the same amount I was earning as a GTA: $500 per month. So I divided 500 by 30, the number of days in a month, and got $20 per day, which is actually slightly more than the actual math, and I set out each day to make $20 from the sale of my work. And if one day I made $100, that meant it was OK to make nothing for 5 days since I had made 5 days income in one day. Soon enough I was making way more than $500 a month, and soon enough I saw the potential for a much better income than the one I was making as a GTA. So, to conclude, if you make a lot of money you are going to have to set new income goals, goals you can reach relatively quickly, or you will get discouraged and most likely quit. You may also want to put aside a cash reserve so you can maintain your current lifestyle while you are earning a lower income and building your business.  JM: How does the photography that you do impact your choice in gear? I know you use multiple formats. Basically, I believe that first, each format has unique capabilities. Second, I consider the size of the final prints I want to make when I decide which camera to use. Small prints means 35mm digital. Large prints, 16x20 and above, mean 4x5. Now this implies that I am aware of what size I want to print specific images while I am working in the field. Most photographers prefer to wait until they return to their studio to make a call about print size. But what you need to understand is that my approach is the approach that painters follow. For a painter, the size of the painting is decided before you start painting because the painting cannot be resized. To me, that is the correct approach for any visual art, including photography. Why? Because some subjects ask to be printed large, and some subjects call to be printed small. You see, print size is not just a matter of resolution or camera format. It is also, and foremost, a matter of subject matter. You have to take into consideration what your subject calls for in terms of print size. And if the subject calls for a small print, then there is no point using 4x5. Similarly, if your subject calls for a large print, there is no point trying to enlarge a 35mm file beyond what is a reasonable enlargement, which is about one print size above native resolution. You are much better shooting the image with 4x5 and getting much better detail and resolution to begin with. This is my approach, and it is an aspect of my work that people have a difficult time fully understanding. There is a myth in photography that once you go up to a certain format, and this format in my situation is 4x5, you cannot go down to a smaller format, or if you do it means you are no longer a professional, or you are turning to the dark side, or you are lowering your standards. The fact is that there are different tools -different cameras- for different jobs, and a true professional knows exactly which tools, which cameras, to use in each situation. So to me using different camera formats is the mark of a professional, the mark of someone who is thinking on his feet, in the field, all the way to the final print. JM: Can you talk about what your photographic day looks like? How does your family fit into it? AB: Since I work with Natalie my family and my business are very close. I have a very specific schedule that I adhere to, but I get to set my own hours, which is very nice. I don't know that there is a typical day, but we usually start by discussing how things are going and what we need to do for the day, then move on to doing just that. We take phone calls and receive orders. If we have a show scheduled for that day, or for several days, then we either do the show together or only one of us does the show while the other tends to other matters. During workshops, we both teach together so in this sense we are always traveling together. It is the same when I photograph, something which occupies a very important part of my schedule, and during which I always work with Natalie. It's always the two of us. I used to photograph a lot by myself, but I no longer enjoy it. I just get lonely. I like to have someone with me to share the experience! JM: How do you feel about the evolution of digital photography? AB: I think digital made me successful, and I think it continues to make me successful. So I expect a lot from the evolution of digital photography. I think this is the last form of photographic recording we will see in our lifetime. We had film, now we have digital. We won’t see a third method of recording photographic images in our lifetime. In fact, there may not be a third form, at least not in terms of images on paper. Analog or digital, that’s it. I am in the process of writing an essay that details this change. Look for it on my website when it is published which should be in Spring 2006. If you are interested in learning more about Alain Briot, you can visit [url= http://beautiful-landscape.com/] http://beautiful-landscape.com[/url].

|

|

|

Re: Part I: Alain Briot Interview with NWP

[Re: James Morrissey]

#35799

Re: Part I: Alain Briot Interview with NWP

[Re: James Morrissey]

#35799

07/17/11 04:26 PM

07/17/11 04:26 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

Editor's Note: We are trying to develop a community where photographers can come and discuss nature, wildlife and pet photography related matters. We encourage you to enter the forums to share, make comments or ask questions about this interview or any other content of NWP. Part II: The Business Aspects of Photography  JM: When was the first time you were published? AB: It was in France, in 1981, in the context of my first exhibition which was at the Journees Internationales de la Photographie in Arles. This is an event that has an international audience, and we were having a group show organized by Scott McLeay. The show was the culmination of his workshop series, which took place in 3 parts. Part 1 was an Introduction to Photography, part 2 was Advanced Photography, and part 3 was creating a Group Exhibition, all the way from conception to shooting to printing, under Scott's supervision in his own darkroom, to exhibiting in Arles. We received a lot of exposure and were published in a number of magazines and newspapers. JM: How long did it take you from your first photographs to become regularly published? AB: Until I decided to do photography full time I did not actively seek publication. Instead, I exhibited my work and publication was in the form of articles written by writers -journalists, reporters, etc.- about my work and myself. This happened pretty much right away, with my first show as I just described. When I started doing photography full time I focused on selling fine art prints, and again did not seek publication. I think regular publication really started when I met Michael Reichmann and he suggested that I write essays about photography. Michael started by publishing a portfolio of my work on his site under the "Guest Photographers" section of luminous-landscape.com I then proceeded to write a regular column for his site that Michael titled "Briot's View." So in this sense Michael was my first regular publisher. In the beginning I wrote reviews on photographic equipment and software. Later, Michael suggested that I write a series on Photography & Aesthetics. At first, I was not sure how to approach the subject so I outlined an 8 part series which addressed each of the main areas of Photography in regards to aesthetics. I then expanded the series to 11 to include essays on personal style and being an artist. The last essay in the series, which is proving one of the most difficult to write, is Being an Artist in Business. We are also starting a new series this December, also on luminous-landscape.com, titled “Reflections on Photography as Art.” I am very excited about this series because it focuses on one of the areas that interests most in photography today. Now, I am published regularly on the web. My essays have been translated in about 10 different languages (I write in English) and are linked to, or re-published, by hundreds of websites worldwide. I am also my own publisher. I publish a large number of essays on my website, beautiful-landscape.com, written by myself as well as by other photographers, usually students. I try to bring new content once or twice a week. JM: How did you go about approaching the magazines and other publishers when you were first starting? AB: I just made submissions by mail. But it never was a primary goal of mine to be published in magazines. My goal was to create and sell fine art photographs and I much preferred to have a show of my work than see my photographs reproduced in magazines. It is only when I started writing articles on photography that publishing, in print or on the web, became a primary goal. JM: How would you recommend this today? AB: It really depends on what your goals are. I think the web is a fantastic vehicle, if you like the immediacy of this medium, which I personally do. Print works very well for some photographers, although if you seek quality reproduction -fine art quality- you are limited to a few magazines who are willing to spend the extra time and money to achieve high print quality on offset presses, something which is truly challenging. And of course there is the business side of it. Being published In a magazine may is not necessarily financially rewarding unless it becomes a regular, day in day out, outlet. JM: You are based in the SW in Arizona. Do you feel it is possible to be a professional nature/wildlife photographer today without spending a minimum 5 months a year on the road? AB: It doesn’t have to be on the road, it can just be photographing near where you live, which is what I have done so far since I have always lived in the landscape I photograph. But yes, I think 5 weeks, which is just over a month, would be a bare minimum. In fact, you really need to photograph year round, not just once or twice a year. I think that is the most important. Even if you can spend only a day a week, it is the regularity that counts just as much as the quantity of days you are out there photographing. Photographing regularly, every week, is one of the things that will make you improve and be successful. JM: How do you balance your family with such an intense schedule? AB: Natalie and I work together. We both do photography and have no other commitments. This is the key to success in our instance. I couldn't do it alone at this point, we are just too busy. It also allows me to focus on the creative part of photography while Natalie focuses on other aspects of our business. JM: How does your website play into your business? AB: It is one of the two primary vehicles for people to discover my work. The other one being shows. In terms of numbers I would say the two are evenly balanced. However, each venue presents unique challenges. The challenge on the web is to express the quality of a fine art print using a medium that varies from computer monitor to computer monitor. Not everyone one sees the same colors, contrast and densities because each monitor is differently calibrated. In print, everyone sees the same quality. And at a show, people see the finest quality because they are looking at actual prints and not reproductions. As a result, the comments I get the most when people purchase my work over the web is "Wow! It liked it on the web but I really love the actual print! It is so much better than I thought, and I thought it was beautiful already on the web!" So basically, making people aware that a computer monitor is only an approximation of what a fine print is really like, is the key to success here. JM: Please describe what your business looks like currently - what are your primary sources of income photographically? And What other sources of income do you live off in the photographic business? AB: My main income comes from fine art prints. For a long time this was my only source of income and I did not think I would actually do anything else. But through becoming successful I found myself with extra time on my hand and at that point I had two choices: I could continue creating and selling fine art prints and then occupy the rest of my time with hobbies, or I could return something to the photographic community as a whole. I chose the second option and created a series of workshops designed to give the opportunity for photographers to study in a short time what took me years to learn. In short, the goal was to avoid having others go through what I call "the school of hard knocks," the trial and error process I had to go through because I had to learn so much on my own. The program, because it is a complete program, includes photographing in the field, studio work focused on crafting a fine art print, matting and framing, and finally learning how to market and sell your work. When looked at as a whole, a photographer serious about starting a career selling fine art photography can, in two years or less, learn everything they need to know to get started. Of course, I cannot guarantee a specific income, as this is based on variables that are not within my control, such as the economic strength of a specific area, the motivation level of each participant and more, but what I can say is that the program is available and is, to my knowledge one of a kind because it is taught by someone who has done all of this himself successfully. Certainly, other photographers teach these subjects for other areas of photography such as stock sales, but in regards to selling fine art photographs, I know of no one else who offers a similar program.  Recently, I added a CD series called Alain's Photography Tutorial CDs to complement the program. This series allows photographers who prefer not to travel or do phone consulting to benefit from this program. It is also a way to get introduced to my essays, to read what my views on photography are, and to familiarize yourself with my teaching approach. Finally, I also offer supplies for photographers who wants to use the exact same materials I use to craft my fine art photographs. Currently, these include portfolio cases and matting. Again, the idea is to allow photographers to do what I do in a much shorter time, and allow them access to materials that are not easily available or are unaffordable. For example, to have a portfolio case made, in the same quality as the cases I use, would cost you $700 per case if you had only one or two made, which is all that most photographers need when they are starting out. It would also take you two months of work. With us, you can place an order and have it delivered immediately, and you only pay a fraction of this cost. In regards to our teaching, it is important to know that both Natalie and I are professional instructors. For us, offering workshops, seminars and instructional materials is a fantastic opportunity to use our second source of knowledge, the first one being creating art. Natalie has a Bachelor Degree in Education and taught art at the Junior High level for 10 years. I studied all the way to the PhD and taught Writing, both creative and technical, as well as Photography, both chemical and digital, for over 7 years at the University level. When we designed our workshop program, we decided that it would include a very strong teaching component. In fact, we centered this program around our teaching. Certainly, with field workshops, the locations we visit are very important and we select only the most photogenic locations. However, we teach photography each and every day during workshops, through lectures, presentations, one on one work and more. To us a workshop is a learning opportunity for participants and a teaching opportunity for us. We love to teach and Natalie and I each have a different approach. Natalie focuses more on teaching art and is extremely patient with each participant. I focus more on photography and on how art and photography are related, and give more field lectures and presentations. The success of this program has been just as extraordinary as the success encountered by my fine art prints. We have had numerous students tell us how much they enjoy our workshops. A look at the testimonials on my site will show you exactly what they say. We also have had a number of photographers become extremely successful with their photography, starting to exhibit their work after working with us, or starting to sell their work. One of my students, Jason Byers, even opened his own art gallery. Many others manage their own web sites, such as Jeff Ball (html), Keron Psillas (html) and many others. I also have a section on my site where I display students’ work called the Students Gallery. Finally I am very proud of the essays that students have written about their work, essays that are published on my site in the Thoughts & Photographs series. As a whole, Natalie and I have been very impressed with the quality of the work produced by our students. To us, this is both very exciting and very rewarding. A long time ago I read a comment made by John Sexton in response to the question "Why do you offer workshops ?" John answered that he offers workshops because he learns so much from students. When I first read his answer I did not believe it. Now, I know it is true. I have learned an immense amount from teaching. I cannot use all that I learned, but I am a better person because I learned it. This is not knowledge gained for profit. This is knowledge gained for personal growth, knowledge gained from teaching what you love, which is my instance is photography, to someone who really wants to learn it and excel at it. To me this is priceless, and I feel privileged to be in this situation. It is also important to know that effective teaching is not something that everyone can do. For one thing, it does require training. This is a rarely discussed aspect of offering workshops. Many believe that all it takes is being a good photographer. I wish that was the case. The fact is that one needs to be both a good photographer and a good teacher. A good teacher is someone who is able to explain what they do and why they do it to others. A good teacher is someone who is able to reflect on their teaching. A good teacher is someone who remembers how the good teachers he studied under treated him. A good teacher is someone who cares for others. At this time, in regards to our workshop program, we have over 70% return participants. There is only one reason why people keep coming back, and that is because they enjoy the experience.  JM: A big area of photography that is not covered is business education. Have you had education in regards to running a business? If so, what portions of a business education do you think are absolutely necessary for a person to be able to run a profitable business? AB: I had business education and I consider it indispensable to do what I do. Not having it would be like trying to do scuba diving without proper training. In short, it's asking for trouble at best and drowning, at worst. In my case, my studies did not focus on business at all. So I attended workshops outside of the university setting to learn that aspect of running a photography business. The first workshop I ever did in this regards was offered by someone called Libby Platus. This workshop was titled "The artist in business, taking care of you own destiny." I was a GTA then, and the only reason why I attended it was because it was a free workshop, organized by the local chamber of commerce to help local artists. If I had to pay I could not have afforded it. Libby taught me the basics of a business approach that I continue to follow today, which is taking control of your destiny, of your business, rather than hope for the best and rely on outside forces to shape your life. Later on, when I became successful selling my work, I hired a private consultant to help me with specific issues I was dealing with at the time. I could then afford to pay someone for this service. The issue I had is that I was selling too much and couldn't produce the quantity of work that I needed. I was always selling out, and therefore running out of prints that people wanted to buy. As a result, I was loosing money. The recommendation this consultant gave me was to raise my prices, basically using a simple marketing approach which is to control the volume of work sold by the price. He also told me to stop selling my smallest print size, which at the time was 8x10 mat size. At first I was terrified at the prospect of doing what he asked. It took me several days, during my next weeklong show, to get around to doing it. But when I finally did something extraordinary happened: the volume of sales dropped only slightly, because people were buying the larger prints right away. So in fact not only was I not losing money, I was actually making more money. I had to raise my prices regularly for over a year to actually get to the point where sales were significantly lowered and I was able to reduce my workload which had become crazy prior to making these changes. This taught me a number of extremely important things in regards to running my business. First, price is not the deciding factor for people who want to buy my work. Certainly, beyond a certain point people would not be able to afford it. But I was far below this point and didn't know it. Second, how many sales I make is not a measure of success. I now make far fewer sales than I did prior to making these changes, yet my income is higher and so is my profit margin. One thing I did recently, for web sales, which as I explained are challenging because customers can't see the actual print quality, is introduce the Print of the Month Collection which is a collection that I only offer over the internet. Photographs in this collection are offered at a unique price, lower than my regular prices. The goal is to offer an affordable entry point for collectors to experience my work. Many later collect larger pieces because they know what the quality of my work is really like. I do not offer this collection at shows because collectors can see the quality of the work first hand. This collection is extremely well received. The conclusion to be drawn from my experience offering low-price photographs at first then moving to more adequate prices later on, is that an artist has to make a choice between quantity and quality. It can be one or the other, but it can't be both. When I was selling a quantity of prints that exceeded my production capabilities, quality was starting to suffer. I don't think we got to the point where there actually was a drop in quality, but we would have got there eventually. After we reduced the quantity of sales, by increasing prices and increasing the size of the smallest prints we offer, we were able to not only prevent a drop in quality, but also to increase quality significantly. Today, we are offering the highest quality prints we can produce. While there is always something that can be done better, we are doing everything we can think of to guarantee that the quality of the work we sell is the finest we are capable of producing. We spare no expenses in doing so. Not only do we use all-archival materials, we have also designed better ways of matting, mounting and framing our work.  We are also able to introduce work that we could never have dreamed of introducing before, such as my Navajoland Portfolio, introduced in December 2004, and my new Antelope Canyon portfolio which I will be announcing soon. These are projects that take an enormous amount of time to complete, and which we could not do if we were not having the pricing structure that we have. From a business perspective, such projects can only be successfully completed if you have the plenty of time available and if you are not rushed. This brings us to a very interesting comment in regards to pricing art. For a long time I had a very difficult time understanding why fine art was so expensive. It was only after I was able to solve the difficulties I encountered when I was doing volume selling, that I realized why fine art prices have to be high. I now understand that prices are high because this is the only way an artist can devote the required time, and purchase the necessary supplies, to produce fine quality work. Since everything is hand made by the artist himself, the workload is huge. Similarly, quality supplies are expensive. When you add the two together you realize why artists who do not ask enough for their work cannot stay in business for very long. Take for example the Navajoland Portfolio, or the upcoming Antelope Canyon portfolio, for which the goal is to produce the finest quality possible, bar none. Simply creating the design and the first model for the Navajoland Portfolio case took over a month. It then took another month to create the 50 cases for the limited edition. A comparable amount of time is required to craft the prints, write the text, print and bound the artist statement, assemble the portfolio, etc. etc. And the only way we can afford to do all this is by having a solid pricing structure, not just for the portfolio, but also for our entire fine art collection. If we lower our prices, we will become unable to offer portfolios. And then we all lose: as artist we are not able to create our finest work. And as collectors we are not presented with the opportunity to own the finest work. The same holds true for everything we offer. For example, we specialize in very large sizes, 40x50 and 40x120 or even larger. Such large prints are extremely fragile when done and must be handled extremely carefully. You cannot take the necessary time preparing them for shipping, or delivering them (which is what I do if collectors live within driving distance) if you are in a hurry or if the volume of orders is overwhelming. The only way you can do it is by reducing the volume so you can increase the quality of the product. Again, it goes back to making a choice between quality versus quantity. When one increases the other decreases. Quality is our choice, and it is one of the best decisions we ever made as artists. JM: Are you involved in the Stock Photography market? AB: Not actively. I do stock sales when I receive a request but I do not actively market my work for stock. I have a notice on my website under "licensing" that describes how my work can be used in this context. If you are interested in learning more about Alain Briot, you can visit www.beautiful-landscape.com/ . As always, we encourage you to come join the community and to be participants in the forums. If you have not registered yet, please do.

|

|

|

Re: Part III: Alain Briot Interview with NWP

[Re: James Morrissey]

#35800

Re: Part III: Alain Briot Interview with NWP

[Re: James Morrissey]

#35800

07/17/11 04:28 PM

07/17/11 04:28 PM

|

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

James Morrissey

OP

OP

I

|

OP

OP

I

Carpal Tunnel

Joined: Feb 2005

Manhattan, New York, New York

|

Part III: The Environment  JM: How do you see the current state of environmental affairs - both at home and globally? AB: I think that the environment is something we need to be concerned about as landscape photographers. After all, it is our subject, and if it disappears, or is damaged beyond repair, what are we going to photograph? So I think that this is an important subject, and one that is not discussed enough among landscape photographers in my view. There’s numerous issues that threaten the environment, and as landscape photographers we are in a position to see the outcome of these issues first hand because we spend a lot of time out in the wilderness looking at the landscape. JM: What do you see as your role, if any, in these issues? AB: I think that most, if not all, landscape photographers want to see the environment protected. The problem, though is finding out how we can protect it, what role we can play in either preventing or stopping the damage. It seems that a lot of what needs to be done is out of our hands, requiring legal action rather than just a love for nature. Most of us do not want to get involved in legal matters, or in lobbying for changes, or even in nature protection movements of one kind or another and that makes things difficult. My impression is that one of the first things to do is to put forth a concern for the environment so as to bring an awareness in the general public that the natural beauty we are photographing, the natural beauty we are sharing in our work, is at risk, is under attack, and may not be there forever. This is especially the case for amateur photographer, meaning photographers who do not make a living from their work. Let me explain. Professionals are quite often involved in one nature protection movement, or association, or another, because it is a logical outlet for their work. Even if they are not paid for the use of their images, or are paid relatively little, this is a good way to promote both their work and the work of various environmental groups. And again, there can be a good source of income from this type of venue. So at that level, we can say that many professional nature photographers see their images used towards protecting the environment in one way or another. From there it is only a step away, for these photographers, to talk about how their images are being used, and from there to taking a position in regards to specific environmental issues. Usually, this position is local, rather than global, since it is related to using photographs of specific places. When it comes to amateur landscape photographers, meaning photographers who do not make a living from their work, relationships with environmental groups, or associations, is far less common. That is often because amateur photographers see a gallery, or an art show, or again a stock agency, as choice outlets for their work. Amateur rarely engage in active marketing, i.e. contacting environmental organizations directly in this instance, preferring to rely on venues that already have a built-in channel for selling photographs. Galleries, art shows and stock agencies have such a built-in channel. They not only expect submissions, they depend on these submissions to make an income. But other organizations, such as environmental protection groups, do not have such a channel. Submissions are not so frequent, and when they take place there is no application form to fill in, no specific person to contact, and so on. One must make the call and work things out on a case-by-case basis. It takes a lot more motivation and self-assurance to contact an environment organization out of the blue than it takes to fill in an application form for a show, or a stock agency, or even show your work to a gallery owner for whom this is a daily event. All this to say that more work is involved, and that the benefits are not obvious and may not be financial at all. But, the benefit is that one helps bring attention to environmental causes, and one does bring attention to one’s own work, so in that respect it is a win-win situation. And many things can be worked out once such relationship is started, things that can benefit both parties, such as a show in which a percentage of the proceeds from the sale of the photographs is donated to a specific environmental protection group. This is a very simple approach, and one that is rarely, if ever, turned down as it is clearly a win-win situation.  I also think there are many things we can do personally. For example, now that we are seeing the introduction of hybrid-fuel vehicles, driving a hybrid car or SUV is an excellent way to show our concern for the environment and to take an active role in reducing damage coming from burning fossil fuels. I understand that hybrid vehicles are still more expensive than comparable gasoline-only vehicles, but the difference is bound to get smaller and smaller. We can also expect more practical hybrid vehicles, such as 4x4 SUV’s or trucks, something necessary, at least for me, to reach the locations I am photographing. I would definitely buy a hybrid 4x4 medium-sized truck if one was available. Knowing that I am helping reduce emissions by driving it would be enough for me to rationalize this purchase. The fact that it would save me money on fuel in the long run would be secondary, though important as well. I do think that as nature photographers we need to first, become aware of how much the vehicles we drive damage the environment through the exhaust gases they emit. On average, photographers drive some of the largest 4x4, trucks or SUV’s. Photographers also drive a lot of miles each year. So moving to hybrid trucks, SUV, or cars if you don’t need the larger size vehicle, would definitely be a huge step forward. Not only that, but it would set an example by showing to others that our concerns for the environment is demonstrated by our adoption of hybrid vehicles technology. I think we owe it to our subject -to nature and to the environment- to make that one contribution, that one change. Another thing we can do is take an active role in not damaging the environment any more than it already is. I personally do not drive off road or hike off trail in fragile terrain, such as cryptogamic soil, and I also pick up any litter that I find along my way. I know this may sound like small steps when compared to larger problems like acid rain, global warming, or damming a river, but these are steps I can conduct myself, and which do make a difference if they are conducted by a large number of people. I also own land that I keep in a natural state, undeveloped, and which I purchased for its photogenic qualities. Natalie and I own three 40-acre parcels at this time. It may be a drop in the bucket, but again it is something I can do. JM: Are there any organizations that you specifically feel are doing great work at protecting the environment? AB: I hesitate to recommend specific environmental organizations. I feel that what is most important is that if you choose to support such an organization, you select one that is willing to work with you, and preferably one that is located near where you live, or has an office near where you live, and is working on protecting an area that you are able to photograph so that you can work with them and make use of your photography. JM: Hybrid SUVs are seen to be great for city dwellers. Do you see a significant difference in fuel economy living in a place like Arizona?. My wife and I are debating a move to Wyoming and have been considering an Escape Hybrid. However, I am concerned that most my mileage will not be City driving. AB: I am most familiar with the Toyota Hybrids, both the Prius and the Highlander Hybrid, which to my understanding have the highest mileage per gallon of all hybrids, and from what I know the fuel efficiency is excellent both in the city and on the open road. I think that, in terms of maximizing fuel efficiency with a hybrid vehicle, what matters most is not where you drive it, but rather how you drive it and in this regards it is our driving habits that we have to work on. For example, accelerating and decelerating progressively, rather than suddenly, are key to increasing fuel economy with a Hybrid, and this approach is totally different than driving a muscle car, to go to the extreme, or driving in a "racing" fashion, or again an aggressive fashion, to try and describe some of the different driving habits that are out there. In this respect we may have to get out of our collective unconscious the fact that to be accelerating and decelerating progressively is neither passive or submissive but rather responsible and oriented towards fuel economy. Our speed of travel is also key, and driving at the speed limit, rather than as fast as we can get away with, is also key to maximizing fuel economy. In other words, our lack of concern for fuel consumption, as a society, is not reflected only in our choice of vehicles but also by our driving habits and styles. We need to change more than just the cars we drive.  There are many myths out there in terms of what Hybrids can do for us in terms of helping us save fossil fuels. I mentioned to a friend recently, after he remarked that the environment was getting more and more damaged, that he should get a hybrid vehicle. His response was that "Hybrid cars are coming too late." My reply was that they were coming just in time. Sometimes I think that there is a feeling of helplessness in front of the problem on the part of a number of people, and that they don't realize how much of a difference they can make should they decide to be pro-active rather than passive. This person, who is concerned with the environment, went on to buy a new gasoline only car, and spent as much as if he had bought a Prius Hybrid. In fact, the car he chose was very close in shape and size to the Prius... If you are interested in learning more about Alain Briot, you can visit [url= http://beautiful-landscape.com] http://beautiful-landscape.com[/url]. As always, we encourage you to come join the community and to be participants in the forums.

|

|

|

|

|

0 registered members (),

275

guests, and 3

spiders. |

|

Key:

Admin,

Global Mod,

Mod

|

|

|

Forums6

Topics628

Posts992

Members3,317

| |

Most Online876

Apr 25th, 2024

|

|

|